|

| |

|

|

|

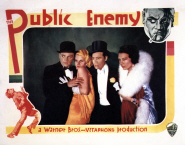

Warner Bros. & Vitaphone, 1931.

Directed by William Wellman. Camera: Devereaux Jennings. With

James Cagney,

Edward Woods,

Jean Harlow,

Joan Blondell,

Donald Cook, Leslie Fenton, Beryl Mercer, Robert O'Connor, Murray Kinnell,

Frankie Darro, Purnell Pratt, Robert E. Homans, Eddie Kane, Sam McDaniel,

Mae

Clarke, Rita Flynn, Ben Hendricks, Jr. |

|

The deadly chatter of machine guns and the piercing screech of automobile tires

on vehicles wildly careening around the corners of city streets were among the

most iterative noises that blared from the screen in the years immediately

following the introduction of sound. These were the characteristic noises that

accompanied the wave of gangster films that came, like a swarm of hornets, with

this new element. The deadly chatter of machine guns and the piercing screech of automobile tires

on vehicles wildly careening around the corners of city streets were among the

most iterative noises that blared from the screen in the years immediately

following the introduction of sound. These were the characteristic noises that

accompanied the wave of gangster films that came, like a swarm of hornets, with

this new element.

Historically, there is a question whether the big rush

of films about crime and the folkways of racketeers and gangsters, which was a

major manifestation in the culture of American films, would have come―at least,

in the volume and with the overwhelming impact that it did in the early

1930's―without the dimension of sound. It is obvious that the

physical propulsion and shock effect of these films, good or bad, were due in

large measure to the newness and amazement of having one's ears filled with

noises of crime and the unaccustomed lingo of the tough guys, their lurid jargon

and their punctuating snarls.

But of equal historical reason for this outbreak of

gangster films was the simultaneous conjunction of two major social trends. The

surge of organized crime that came in this country in the 1920's as a

consequence of the Prohibition law and the inducement it gave to the expansion

of illegal traffic in beer and liquor reached an explosive climax in 1929 with

the St. Valentine's Day massacre in Chicago. This horrifying incident, in which

a whole platoon of gangsters was lined up against a wall and shot by a firing

squad of rivals, finally brought home to a torpid nation the immensity and

ferocity of organized crime.

In that same year, the flimsy figment of financial

prosperity and the illusions of endless luxury that went with it came tumbling

down in the great Wall Street crash which prefaced the terrible Depression of

the next few years. This shocking and soon too-painful notice that our vaunted

security had been based on faulty economics and deceptive salesmanship

disillusioned the public and left large segments of it prone to the cynicism and

rebellion that whined and snarled in the gangster films.

Significantly, the movie-makers―and the novelists and

playwrights, too―had been slow in discovering and deciphering the surge of

organized crime. The first novels on this subject did not come until the

mid-1920's. The first stage play to treat it realistically was Broadway in 1926.

The first film to identify the Prohibition gangster was

Josef von Sternberg's

Underworld, turned out in 1927 from a scenario by a Chicago newspaperman, Ben

Hecht. It was followed the next year by such items as The Drag-Net, The Racket

and Dressed to Kill, all silent and un-sensational as statements of a sweeping

social plague.

But with the coming of sound and the prompting of

mounting crime waves and massacres, the gangster film suddenly broke the barrier

and became a dominant genre. Ten or twelve of them were turned out in 1929. Scores came along in 1930 and 1931. The coupling of them with the headlines and

with the awareness of such new kings of crime as Al Capone, John Dillinger and Owney Madden caused them to seem real exposés, vivid and true-to-life

reflections of what was happening in the blazing underworld. The fact that they

were mostly overstatements, blatant compendia of clichés picked from the

journalists of gangland, was not sensed by the public at first. They satisfied a

morbid curiosity. Also, they moved excitingly; the action scenes were usually

shot with mobile silent cameras, and sound effects, were added later on.

The most important thing they did, however―the three

or four great ones, that is―was give a fearful intimation of the nature of the

gangster mind. This notorious criminal individual, what sort of creature was he,

with his brazen proclivity to private warfare, his willing exposure to mortal

peril and his readiness to betray his partners, all in his passionate quest for

power? He was an awesome enigma, the modem-day badman of the West, but with a

difference. He was a consequence of societal conditions. The public wanted to

know about him.

The first classic revelation is that given by

Edward G. Robinson in

Little Caesar, made by Mervin LeRoy for First National (Warner

Brothers) in 1930. It is a brilliant and chilling picture of a sardonic and

sentimental Italian-American, modeled more or less on Capone, who goes after

power with a vengeance and is betrayed and destroyed in the end. Robinson's Ricco (Little Caesar) may be a fictional character, skillfully realized by the

actor from a script by W.R. Burnett, but he is consistently concentrated and he

is believable.

_NRFPT_01_small.jpg)

However, Ricco comes at us fully fledged and

professionally skilled. He is a postgraduate criminal when the picture begins.

Therefore, I find a better drama and, indeed, the most compelling gangster film

to be The Public Enemy, made by William Wellman with

James Cagney in the leading

role and released by Warner Brothers six months later, in April 1931. This is

the first one to offer speculation on how the gangster evolved, his social

origination and his seduction into a life of crime and then into gangland

complications by the opportunities that society itself held out, all with

incisive graphic detail and illustration of corrosive character. However, Ricco comes at us fully fledged and

professionally skilled. He is a postgraduate criminal when the picture begins.

Therefore, I find a better drama and, indeed, the most compelling gangster film

to be The Public Enemy, made by William Wellman with

James Cagney in the leading

role and released by Warner Brothers six months later, in April 1931. This is

the first one to offer speculation on how the gangster evolved, his social

origination and his seduction into a life of crime and then into gangland

complications by the opportunities that society itself held out, all with

incisive graphic detail and illustration of corrosive character.

It follows the standard format of all the early

gangster films —the

initial insignificance of the hero, his strategic thrust for power, his brief

enjoyment of underworld preeminence and then his sudden, ignominious rubbing

out. The devices for these steps may have varied, but the consequence was always

the same. In The Public Enemy, however, the inspection of the hero's life begins

much earlier than usual. It begins with his boyhood in a Chicago slum, child of

a widowed Irish mother and pal of a swayable scamp with whom he fetches pails of

beer for neighbors and shoplifts in big department stores. In a 1909 urban

environment, which Wellman pictorially describes as a welter of crowded streets,

stockyards, beer wagons, corner saloons and Salvation Army Bible-thumpers, the

youngster is already launched as a vandalistic mischief-maker and a committer of

petty crime.

Now it is six years later, in the chronological

phasing of the film, and our hero, Tom, and his pal are pool hall roughnecks,

ready to move along under the tutelage of a small-time Fagin, a sleazy character

named Putty Nose (whose pastime is playing "I'm Forever Blowing Bubbles" on the

tinny piano in the back room), to the intermediate step of a fur robbery and an

initial ugly tangle with the police. Now the role is taken by Cagney, a small,

wiry, impudent youth (or apparent youth, at this stage), and the character

begins to take form. Tom is a hard, brazen, cheeky little ruffian, schooled for

a criminal career and contemptuous of the patriotism of his older brother, who

is prepared to go off to the First World War.

Wellman indicates clearly that his delinquent gets

caught in the pull of big-time crime because he and his pal are available to do

jobs for the barons of booze who are bootlegging illegal liquor to the good

citizens crying for it. A shot of crowds of bottle-smuggling home goers on 1920

New Year's Eve makes the point that Prohibition made lawbreakers of the citizens

and stimulated the traffic the professional criminals battled to control. Tom's

introduction to it is through a caper whereby he and his pal, Matt, are assigned

to steal booze from a warehouse by siphoning it out of vats into a gasoline

truck and making off with their haul in a hail of gunfire. After this, Tom is on

the move. He abandons the cheap cap of his boyhood. He gets outfitted in

tailor-made clothes, with snap-brim hat and camel's hair coat. He is a slick,

sporty, on-the-way-up punk.

Thus our underprivileged slum boy, who might have gone

on to a bleak career of common crime if it hadn't been for Prohibition, is now

involved in this new nefarious trade, which is practiced openly and boldly, with

the paid-off connivance of the police, and is given such social encouragement

that Tom can boast of his connections to his family. The fact that his brother

scorns him when he returns wounded from the war is only further indication that

his brother is a sap.

The requirement of this new brand of criminal is that

he conform to the mores of the mob, that he take orders―kill, if he is told to,

or put himself in the way of being killed. The enemy is the rival outfit, which

is more assertive and formidable than the police. The maintenance of equilibrium

is according to tacit rituals and codes. But such is the nature of the

"business" and such are its possible rewards that it aggravates ambition,

stimulates a hunger for power. The meanest qualities of the individual are

brought out by the competitive atmosphere. Moves to upset the equilibrium result

from changing attitudes. It is change in the individual that is the foremost

fascination in the gangster film. And it is this manifestation of evolution that

Cagney does so well.

His tough little guy, who stands so boldly with his

feet spread, his head drawn back, his arms by his sides and extended outward

with the fingers half clenched in fists, is an image of fierce determination and

tightly controlled energy, and his quick, gravelly way of speaking conveys

impertinence, impatience and brusque command. You see in him from the beginning

a piece of human machinery that seems geared for no other action than that of

propelling itself, rapidly, smoothly, quietly and satisfactorily to itself

alone. He has the grace of a prizefighter or a dancer. This isn't surprising;

Cagney was both before he came into motion pictures in 1929.

_NRFPT_02_small.jpg) But what he slips into the role so slyly and with such

chilling effectiveness is a sense of the change of the gangster into a species

of fiend. This is best illustrated in the film's most original scene, which is

now one of the most famous and most often cited in gangster films. It is that in

which Tom and his first mistress, acquired as a status symbol of his rise, are

having breakfast in their cluttered apartment. He looks cheap and dime store

tacky in his rumpled silk pajamas; she looks dull in her dressing gown. The

atmosphere reeks of Tom's boredom and restlessness. In an attempt at refined

conversation, the mistress, played by

Mae Clarke, asks him what he would wish. He

looks at her coldly, and, with a mean smirk, he snarls, "I wish you was a

wishing well; then I could tie a bucket to you and sink you!" She whimpers

foolishly, "Maybe you've found somebody you like better." For a moment, he

doesn't move. Then he calmly picks up the half of grapefruit from his plate and,

with a sudden, vicious forward thrust, as though throwing a punch, shoves it

squarely and forcibly into her face. But what he slips into the role so slyly and with such

chilling effectiveness is a sense of the change of the gangster into a species

of fiend. This is best illustrated in the film's most original scene, which is

now one of the most famous and most often cited in gangster films. It is that in

which Tom and his first mistress, acquired as a status symbol of his rise, are

having breakfast in their cluttered apartment. He looks cheap and dime store

tacky in his rumpled silk pajamas; she looks dull in her dressing gown. The

atmosphere reeks of Tom's boredom and restlessness. In an attempt at refined

conversation, the mistress, played by

Mae Clarke, asks him what he would wish. He

looks at her coldly, and, with a mean smirk, he snarls, "I wish you was a

wishing well; then I could tie a bucket to you and sink you!" She whimpers

foolishly, "Maybe you've found somebody you like better." For a moment, he

doesn't move. Then he calmly picks up the half of grapefruit from his plate and,

with a sudden, vicious forward thrust, as though throwing a punch, shoves it

squarely and forcibly into her face.

This was and remains one of the cruelest, most

startling acts ever committed in a film―not because it is especially painful

(except to the woman's smidge of pride), but because it shows such a hideous

debasement of regard for another human being. This simple act swiftly changes

the audience's feeling for Tom, erases the expectation that he may by some

miracle be redeemed. From here on, we know he is committed to power and

violence, to his own private route of self-advancement and self-indulgence,

which does not even have room for his pal, Matt. He is a vicious little monster,

still fascinating to watch, but as erratic, unreliable and dangerous as a

fer-de-lance.

We watch him go out now and make contact with a

dazzling, slippery blonde, played voluptuously by young

Jean Harlow, and we are

engrossed and amused by the fulfilled prospect of fireworks and treachery here.

We watch him move in on the layout of his fallible confederates in crime and

ruthlessly, icily bump off his old boyhood preceptor, Putty Nose. This is a fine

scene, incidentally, with the camera cutting away from the victim and panning

around the room as Tom shoots Putty Nose at the piano; there is a jangled

termination of the old "Blowing Bubbles" song; we hear the thump of the body as

it hits the floor, and then the camera comes full on Tom's face as he says

casually to Matt, who is with him, "Guess I'll call up Gwen. She may be home

now."

We laugh at the utter bizarreness of Tom, in a riding

costume, going to the stable in the suburbs where the horse that threw and

killed his big shot friend, Nails Nathan, is kept, at the outraged swagger with

which he breezes into the barn, and then at a shot from the inside, which tells

us that this ruthless little brute has actually taken gangland vengeance on a

horse! There is grotesque humor in this action, but there is a sobering irony,

too, for it tersely says that this hardened gangster knows no difference between

people and animals. Furthermore, he has no compunction about shooting whatever

he doesn't like.

Such is the concept of this strange breed that Wellman

and Cagney present. The gangster, in his soaring egotism, becomes a frenzied

anarchist. This creature, whom the public has fostered, is inevitably the

public's enemy.

His elimination is standard. First his sidekick, Matt,

is mowed down in a running gun battle with rivals. Tom abandons Matt to his

fate. Then he himself is riddled in a fated fusillade. As he staggers away from

this encounter, bloody and soaked by rain, he mumbles his first acknowledgment

of vincibility: "I ain't so tough."

_NRFPT_03_small.jpg) _NRFPT_05_small.jpg) But Wellman and the authors have concocted a final

retributive twist. They have planned it so that Tom is only wounded in that

penultimate clash. He is taken to the hospital, where he and his brother are

mawkishly reconciled, and arrangements are made for him to come home to mother

to recuperate. To welcome him home, the family gathers; and, when there comes

the knock at the door, the brother throws it open. There, standing in the hall,

is the stiff form of Tom, swathed in bandages like a mummy out of a tomb. For a

moment, it appears the living person. Then, as it starts to fall face forward

into the camera, we sickeningly see it is a corpse and realize that Tom's

gangland enemies have taken grisly vengeance on him. But Wellman and the authors have concocted a final

retributive twist. They have planned it so that Tom is only wounded in that

penultimate clash. He is taken to the hospital, where he and his brother are

mawkishly reconciled, and arrangements are made for him to come home to mother

to recuperate. To welcome him home, the family gathers; and, when there comes

the knock at the door, the brother throws it open. There, standing in the hall,

is the stiff form of Tom, swathed in bandages like a mummy out of a tomb. For a

moment, it appears the living person. Then, as it starts to fall face forward

into the camera, we sickeningly see it is a corpse and realize that Tom's

gangland enemies have taken grisly vengeance on him.

This coldly conclusive image of the fate of the

gangster was enough―or should have been enough―to carry the message that that

sort of life did not pay. But it was questionable whether all the people who saw

this film in the bleak years after its release―the out-of-work men sitting

forlornly in the theaters that were their havens in Depression times, the

youngsters who were fearful of the future―were revolted by it. Did they not feel

with the gangster their own resentments against society? Did they not envy him

his affluence and vicariously enjoy his burst of power?

Many people worried about this, and, in 1931, there

came a wave of public outcry against the showing of gangster films. Pressure

reached such intensity that the motion picture industry was compelled to take

steps to restrict the output. This contributed to the adoption of a Production

Code. At the same time, an excess of crime pictures created audience apathy. The

public soon shoved a grapefruit into the faces of the public enemies.

|

|

The Great Films by Bosley Crowther

G.P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1967 |

|

|

|

Additional detailed information about

this film is available from

the AFI Catalog of Feature Films at

AFI.com, or by clicking

here. |

|

|

|

Additional photos courtesy of Gary,

Frances, and Joe |

|

|

|

|