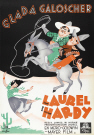

Laurel & Hardy come to Brushwood Gulch in the Wild West to deliver

the deed to a gold mine to the daughter of a recently deceased

partner of theirs. Their enquiries of saloon owner

James Finlayson prompt him to palm off his brassy partner as the

heiress, and taken in by her, they hand over the deed. Later

they encounter the genuine heiress, employed as a kitchen maid in

the saloon, and determine to get the deed back. Their initial

efforts get them run out of town, but a final nocturnal foray into

the saloon crowns their efforts with success.

Laurel & Hardy come to Brushwood Gulch in the Wild West to deliver

the deed to a gold mine to the daughter of a recently deceased

partner of theirs. Their enquiries of saloon owner

James Finlayson prompt him to palm off his brassy partner as the

heiress, and taken in by her, they hand over the deed. Later

they encounter the genuine heiress, employed as a kitchen maid in

the saloon, and determine to get the deed back. Their initial

efforts get them run out of town, but a final nocturnal foray into

the saloon crowns their efforts with success.

With the possible exception of

Sons of the Desert, which was

subtler if not funnier, Way Out West must rank as the best of

all the

Laurel & Hardy features. Not only is it pure,

unadulterated

Laurel & Hardy, with no time

wasted on subsidiary plotting or romantic or musical "relief," but

it is also a first-rate satire of the Western genre. Most such

satires have usually consisted of putting a comic—Jack

Benny,

Bob Hope,

Martin and Lewis,

Abbott & Costello—through

their customary paces against a Western backdrop, which is often not

exploited at all.

The Marx Brothers came closer to genuine satire with their

Go West, and

Laurel & Hardy,

though denied the budget the

Marx Brothers had and thus limited in their spoofing of

spectacular action sequences, succeed perhaps best of all.

Their characters are beautiful takeoffs on the standard wandering

cavaliers, while

James Finlayson, cast as Mickey Finn, outdoes himself as

the epitome of double-dyed villainy, the sheer joy of chicanery

almost outweighing the monetary rewards it will bring.

Finlayson's direct stares at the audience, often done in direct

counterpoint to Hardy's (Hardy would appeal for sympathy, while

Finlayson's stares were aggressive, as if

daring the audience to do anything with its knowledge of his own

perfidy) here are extended and exploited as never before. As

he outlines some particularly heinous piece of villainy, he

rubs his hands, chuckles, leaps for joy and looks to the audience

for admiration of his cunning; or as he tells some exceptionally

outrageous lie, he stares at the camera with an exaggerated intake

of breath, over-awed himself by his own skullduggery.

There isn't a wasted moment in Way Out West. Even when

the plot isn't being propelled forward, there are delightful little

vignettes and the establishment of running gags. Early in the

film,

Laurel & Hardy,

accompanied by their mule, wade through a river. Hardy's

aplomb, and the position of the camera, tip us off to what is

coming-and, sure enough, he steps into a hidden pot-hole, and

plunges beneath the surface of the water. Familiarity was too

much an essential part of the

Laurel & Hardy

format for it ever to breed contempt, and thus the gag works even

better when it is repeated at the end of the film as a wrap-up, this

time with the comedians walking away from the camera instead of

towards it.

An

amusing, but admittedly rather protracted, early sequence in which

they are confused by a signpost which the wind keeps shifting into

different directions was never included in the U.S. release version,

but was retained in the European prints. (Laurel

& Hardy

films, extremely popular in Britain and Europe, invariably played at

the top of the bill, where the short running times were sometimes a

handicap).

Hitchhiking a stagecoach ride into town, Hardy engages the lone lady

in the coach in some marvelous small-talk. "A lot of weather

we've been having lately," he begins coyly, and adds asininity to

absurdity, the convivial gallant and the intruding bore all rolled

into one, while his captive audience smiles politely, hoping he'll

shut up. Hardy of course is merely seeking to bring a little

old-world grace and charm to this wilderness, and he is rudely taken

aback when they reach their destination. The lady is met by

her husband, the burly sheriff, who asks if she had a nice journey.

Yes, she tells him, except for that awful man who bothered her from

the moment he got into the coach. The sheriff gives the boys

until the next coach to get out of town. With the plot proper

not yet under way,

Laurel & Hardy

still find time to dally outside the saloon, and go into an

extemporaneous and charmingly executed soft-shoe shuffle. It

is performed in one long take, like a vaudeville routine, with an

audaciously obvious back projection screen (cowboys, horses, wagons

going about their business in the dusty street) immediately behind

them. An unexpected bonus later in the film is a second such

musical interlude when, as punctuation between two comedy episodes,

the boys relax in the saloon and sing "In The Blue Ridge Mountains

of Virginia," performed simply and pleasingly, easing into comedy

only for its climax, when Laurel is hit on the head and switches

from a shrill falsetto to a deep base.

The first encounter with the bogus heiress provides some superb

comedy.

Laurel & Hardy,

too trusting and good-natured to see through the sham sweetness and

phony tears of the gold-digging impostor, are entirely taken in by

her. Hardy has cautioned Stanley to break the sad news gently, but

Stanley, unfamiliar with the ways of diplomacy, blurts out the news

with a bald statement and seems pleased with his information.

"Is my poor daddy really dead?" croons the bogus heiress tearfully,

and Stan solaces her with, "I hope so-they buried him!" With

dignity, Hardy rescues the delicate situation and hands over the

deed to the mine. A family locket has to be handed over too,

but this somehow has slipped into his shirt. Stan's efforts to

help Ollie find it soon cause the pair to be hopelessly enmeshed in

a tangle of shirts, buttons, and suspenders, while Hardy, by now in

a state of unseemly dishabille, murmurs his apologies to the

presumably genteel young lady, who is doing her best to express

polite shock, while Finlayson's face can express nothing more than

ill-concealed impatience. Their mission finally completed,

however, the boys leave, only to run smack into the genuine heiress.

The first encounter with the bogus heiress provides some superb

comedy.

Laurel & Hardy,

too trusting and good-natured to see through the sham sweetness and

phony tears of the gold-digging impostor, are entirely taken in by

her. Hardy has cautioned Stanley to break the sad news gently, but

Stanley, unfamiliar with the ways of diplomacy, blurts out the news

with a bald statement and seems pleased with his information.

"Is my poor daddy really dead?" croons the bogus heiress tearfully,

and Stan solaces her with, "I hope so-they buried him!" With

dignity, Hardy rescues the delicate situation and hands over the

deed to the mine. A family locket has to be handed over too,

but this somehow has slipped into his shirt. Stan's efforts to

help Ollie find it soon cause the pair to be hopelessly enmeshed in

a tangle of shirts, buttons, and suspenders, while Hardy, by now in

a state of unseemly dishabille, murmurs his apologies to the

presumably genteel young lady, who is doing her best to express

polite shock, while Finlayson's face can express nothing more than

ill-concealed impatience. Their mission finally completed,

however, the boys leave, only to run smack into the genuine heiress.

Now in possession of all the facts, they rush back to Finlayson's

room and indignantly demand the return of the deed. Finlayson

and his crony, now revealed in their true colors, refuse and a wild

free-for-all develops, with the deed being passed from hand to hand,

and thrown across the room, like a football. For a time, the

deed is safely in Laurel's possession, but the scheming saloon girl,

in a reversal of cliched seduction scenes, chases Laurel into her

bedroom, locks the door behind her, and throws herself on Laurel,

who is cowering timidly on the bed. With the camera recording

the titanic struggle from above, side and from under the bed, Laurel

is finally defeated when the vamp resorts to tickling as a last

measure, and immediately reduces him to a state of screaming

hysterics. One of his funniest variations on their old

laughing routine, it is one of the highlights of the picture.

Rendered quite helpless by this onslaught, he is of no further use

to Hardy—thereafter the girl has only to approach him and he

collapses in hysterics again—and the deed, recovered by the

villains, is locked away in their safe.

Another brief period of repose provides the opportunity to develop

some of the running gags a little further. One of the best

involves Laurel's ability to snap his fingers and turn his thumb

into a flaming torch with which he lights his pipe. Hardy,

despite strenuous efforts, is unable to duplicate the feat, and

finally gives it up as not being worth the bother. Of course,

he achieves success when he least expects it a casual flick of his

fingers later in the film (during a nocturnal foray after the deed)

turns his thumb into a veritable flaming beacon!

The longest single slapstick sequence is retained for the climax,

when Stan and Ollie break into Finlayson's saloon at night.

First comes the problem of climbing into the upstairs window, a

problem solved—apparently—by a pulley system and a mule. As

Hardy sails majestically upwards, Laurel tells him, "Wait a minute,

I want to spit on my hands!" There is a moment's horrified

realization for Ollie before he plummets downwards. Despite

their attempts to be secretive, the howls of pain and ear-shattering

sounds of collapse, collision, and destruction attendant on any

Laurel & Hardy

burglary venture, naturally arouse the nightshirted Finlayson from

his slumbers. Racing up a ladder, Hardy is caught when the

flap of a trapdoor falls squarely on, and over, his head, encircling

it like a millstone. The door is jammed, and there is Hardy's

head, emerging through the floorboards. Laurel grabs the head

between both hands and yanks—and an elasticized replica of Hardy's

head and neck is stretched some three or four feet before

boomeranging back to its original position with a resounding thud.

Finlayson's footsteps are getting nearer, so Stan hides Ollie's head

under a convenient tin pail and scampers away to conceal himself.

Finlayson leaps into the attic with a triumphant bound and surveys

the scene with wide eyes and wrinkled-up nose. As he crosses

the room, .he trips over the awkwardly placed pail. Annoyed,

he aims a furious full-bodied kick at the offending implement.

Thanks to Hardy's ample head being wedged inside, the pail refuses

to budge, and Finlayson hobbles off, nursing his injured foot, while

Laurel tomes out of hiding to ease the pail off his pal's somewhat

battered head.

The final confrontation takes place when the boys take refuge inside

a piano, the tinkling notes tipping off Finlayson that something is

amiss. Stealthily looking inside the piano, he spots his prey,

and nods a confirmation of his discovery to the audience. Then

he sits down and plays a lively jig, each dull thud on the keyboard

telling him that he has hit home. Finally, the piano collapses

in a jangling mass of wires and splintered wood, and the chase is on

again, winding up with Finlayson first hoisted up to a chandelier

and tied there by his nightshirt, and finally trapped in the steel

shutters surrounding his saloon.

Way Out West is 100-proof

undiluted

Laurel & Hardy, and one of their best showcase vehicles.

Even though it inevitably has certain echoes of previous films, it

has no actual repetition of specific earlier gags, and is so crammed

with incident that there is no time for those slowly-developed

milkings of single gags which so often alienated non-partisans of

Laurel & Hardy. Understandably, it was one of their best liked

features.